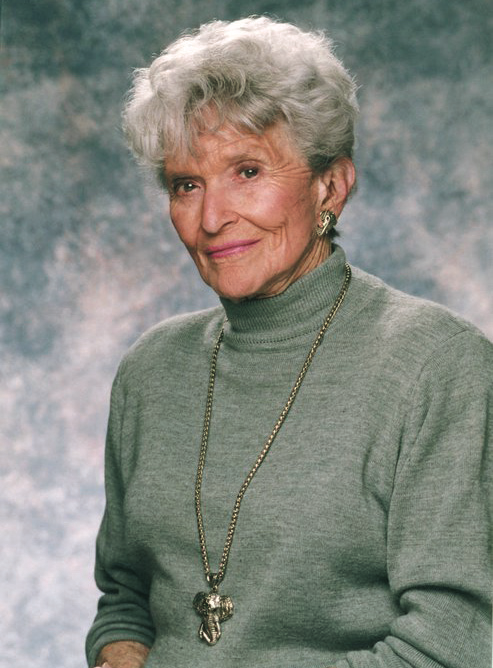

Remembering Marion Downs, (1921 - 2021) Pediatric Audiology Pioneer

There is little chance that any of us will ever forget Marion Downs. Anyone who ever met her can probably remember the precise time and event at which they first saw her, heard her lecture, were introduced to her, or observed her working in the clinic. Marion had the kind of presence that was, indeed, larger than life.

Thousands of professionals worldwide who interact with children with hearing loss are forever indebted to her insight and clinical contributions. Unfortunately, we lost this bright leading light when Marion Downs, MA, DHS, DSc (Hon.), died Nov. 13 in Dana Point, CA, at the age of 100.

It was my good fortune to be Marion’s working partner for nearly four decades. I benefited daily from her buoyant personality and admirable work ethic, and, of course, I was a coconspirator to her many zany antics.

Marion held the title of distinguished professor emerita at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, where she provided hearing services to patients of all ages for almost 40 years.

Throughout this time, she was deeply committed to helping those with hearing loss lead fulfilling lives, as well as educating professionals to understand and support the special needs of this population. Along the way, she earned a welldeserved national and international reputation for her many contributions to the identification and management of pediatric hearing problems.

Ahead of Her Time

Marion was one of the cleverest, most colorful, and most charismatic people you might ever know.

Extremely intelligent, she did not copy or expand on the efforts of others, but rather was one of those rare people whose original thinking led to new clinical conclusions and applications. Her early educational credentials include being named valedictorian of her high school class and elected to the Phi Beta Kappa Society during her junior year of college.

I could write volumes about her lifestyle, personality, humorous antics, liberal political views, incredible crossword puzzle-solving skills, tireless energy, surprising athleticism, occasional bawdiness, avowed feminism, and insatiable love of all things related to hearing.

In fact, one of her favorite stories was about the woman who chummed around with a group of prostitutes and was stunned when they revealed that they were getting paid to do what she was doing for fun. Marion often said that this is how she felt about her work as an audiologist: “If they hadn’t paid me to do it, I would have done it for free!”

Among many other things, Marion will primarily be remembered for her contributions to pediatric audiology. Working with Doreen Pollack at the University of Denver in the 1950s, Marion recognized the paucity of information concerning the identification, evaluation, and management of hearing loss in infants and young children.

According to the prevailing clinical protocol of those early days, 2 years was the youngest age at which one could start with hearing aids and auditory training. Already successfully working with children younger than 2, Marion was devastated when another leader in audiology told her at a conference that no baby should be fit with hearing aids before age 2 because the baby’s unmyelinated neurons would be harmed irrevocably with the introduction of loud sound.

Fortunately, Marion discussed her concerns about this viewpoint with Hallowell Davis, MD, who encouraged her to continue her work with very young children with hearing loss.

Birth of Newborn Screening

Acknowledged as our foremost advocate for children with hearing loss, Marion pioneered the first large-scale infant hearing screening program in the 1960s. Somehow, she convinced the ladies of the Denver Junior League to screen the hearing of babies born in that city between 1965 and 1967. A total of 17,000 babies from eight hospitals were screened.

From that cornerstone research effort, Marion spent the next 30 years in relentless pursuit of making early hearing loss identification in infants an important medical and educational priority. But bringing infant hearing screening to the forefront was no easy task.

Marion faced significant opposition that would have deterred most people. Infant hearing screening was not acceptable to most pediatricians and otolaryngologists in those early years, and even some audiologists expressed negative views of universal infant hearing screening.

Undaunted by the opposition, Marion continued her campaign for early identification and early intervention based on her belief in a critical age period for developing language very early in life. The long and interesting journey to universal newborn hearing screening has been described elsewhere in detail. (Northern JL, Downs MP. Hearing in Children. 6th ed. San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing; 2014.)

Several key developments instigated or supported by Marion finally made the case for mass infant hearing screening:

- In 1969, Marion suggested the formation of the multidisciplinary Joint Committee on Infant Hearing, which would go on to establish screening, testing, and intervention guidelines over the next 50 years.

- In 1993, a National Institutes of Health (NIH) consensus development panel recommended universal infant hearing screening ( NIH Consens Statement 1993;11[1]:1-24).

- In 1995, the research of Christine Yoshinaga-Itano and colleagues documented the validity and effectiveness of early detection and early intervention for infants with hearing loss, confirming the critical age period theory (Semin Hear 1995; 16[2]:115-122).

Marion’s success in bringing the importance of early hearing loss detection and intervention to health policy agencies resulted in our current program, making newborn hearing screening a reality in every U.S. state and territory. This approach has been duplicated internationally as well.

These state-based Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI) programs provide a system of services to diagnose children born with a permanent hearing loss by 3 months of age and arrange for appropriate intervention by 6 months of age. Even more impressive is the fact that 97 percent of the nearly four million babies born in the United States annually are screened for hearing loss prior to discharge from their birthing hospital.

A review of Marion’s extensive curriculum vitae reveals her broad scope of interest beyond infant hearing screening, with publications focused on hearing loss in people with schizophrenia or Down syndrome, and in children with cleft palate; geriatric audiology; perceptual recognition in noise; high-frequency audiometry; the Deafness Management Quotient; sequelae of early and recurrent otitis media; effects of mild hearing loss on central auditory processing; and psychosocial issues for children with cochlear implants.

Many of these topics spawned projects from other researchers, culminating in an increased awareness of the broad effects of hearing loss and benefits to untold numbers of patients.

In addition, Marion was a prolific writer, authoring “The Identification of Congenital Deafness” in 1970; coauthoring with me six editions of Hearing in Children, beginning in 1974; and coediting four editions of Auditory Disorders in School Children with Ross J. Roeser, beginning in 1981.

Changing themes in 2007, she wrote a book aimed at seniors entitled Shut Up and Live! (You Know How): A 93-YearOld’s Guide to Living to a Ripe Old Age, wherein she advises readers to “laugh, exercise, love and enjoy sex, rebel against your aches and pains, and live out your passions.”

Remembering a Legacy

During my last luncheon with Marion a few months ago, she told me that she was indeed “the luckiest woman in the world to have lived such a fulfilled life.” She viewed herself as a “tough old gal” who survived a commercial airliner crash and a close call with a Vietnamese terrorist who tossed an explosive into a jeep coming to pick her up in Saigon, and bounced back anew following the surgical removal of a meningioma when she was 84.

Marion was an exercise enthusiast, jogging daily well into her 60s, skiing in her 70s, and swimming in a mini-triathlon at 89. She won five gold medals for tennis in the National Senior Games. Among my favorite memories of Marion was the fun of cohosting an infamous otology–audiology ski meeting, held annually in Colorado for 30 years.

Perhaps her greatest victory, however, was her success as a woman with a master’s degree working in a competitive medical school environment run by male physician authorities and ultimately earning a full professorship in a surgical specialty department—an amazing accomplishment in her day.

Growing up in New Ulm, MN, Marion likely had no idea where her extraordinary life was headed. How fortunate that when she dashed over to the University of Denver during the summer of 1950 to enroll in graduate studies, the mother of three teenage children skipped the longer registration lines for pre-law, political science, and psychology to choose the shorter line at speech pathology and audiology.

The field of audiology was still in its beginnings as a new profession, and Marion turned out to be very influential in shaping its future directions during the next five decades. Upon her passing last month, condolences arrived from around the world, reflecting the magnitude of her impact on so many.

She was an extraordinary woman, and it is unlikely that we will ever have another like her in our profession. As time passes, she will be remembered for the opportunities she created for all audiologists. She never sought fame or glory, and, in fact, she often blamed others for her acclaim. But above all, she was a great spokesperson for better hearing for every age group.

Throughout her career, Marion was honored by every professional hearing-related organization with an array of awards. Among her many honors are the Outstanding Achievement Award from her alma mater, the University of Minnesota, and Gold Medal Recognition from the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Marion also received three honorary doctorate degrees. She was awarded the Medal of the Ministry of Health of South Vietnam and holds recognition awards from more than 20 countries and governments.

She cofounded the American Auditory Society, International Audiology Society, and Colorado Hearing Foundation; was inducted into the Colorado Women’s Hall of Fame in 2006; and received the Highest Recognition Award from the Secretary of the United States Department of Health and Human Services in 2007.

In 1996, the decision was made to establish a community center in Denver to endow and honor her legacy. Currently, the Marion Downs Center (MDC)’s programs include community outreach activities, such as parent, consumer, and professional seminars; Marion’s Way Preschool; and the unique Connect and Grow Teen Program.

Marion was involved in every aspect of developing the MDC for more than 15 years following her retirement, serving on the planning committee of the new building, participating in fund-raising activities, and personally attending most events. The Marion Downs Center continues to provide clinical hearing, speech, and language services to all age groups.

‘Let’s Have A Party Tonight!’

Marion’s quest for living life to its fullest was nothing short of contagious. She often said, “I have always felt that there was something wonderful about to happen, just around the corner, and it always did. That’s been a really great thing, to have that innate euphoria. It can conquer just about anything that comes up.”

With such a positive outlook, this remarkable woman proved, without a doubt, that the power of one—coupled with tenacity and perseverance, and astuteness tempered with patience and charm—can absolutely move a mountain.

The many accomplishments of Marion Downs will serve to inspire, influence, and encourage others for years to come. There is no question that she changed the world for countless children, families, and professionals.

I will always remember her sage advice: “Live for today, plan for tomorrow, but let’s have a party tonight!”